- Home

- Hubert Fichte

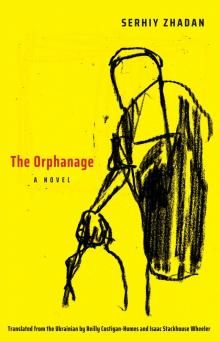

The Orphanage

The Orphanage Read online

Germany in 1942. Detlev has been placed by his mother in a Catholic orphanage. Here, he tries to make sense of the incomprehensible and hostile world outside. What is an orphan? Who was his father? What became of him? What do the dead look like? The dead killed in battle? The dead after an air raid? Why does God not stretch out a net to stop the bombs from falling? How did Christ suffer on the cross? What is a Jew?

The Orphanage begins Fichte’s exploration of sex and sexual identity, an exploration that was to become the dominant theme of his Hamburg novels. Its publication introduces a major post-war writer, acclaimed as the ‘German Jean Genet’.

The Orphanage was awarded the 1965 Hermann Hesse prize.

Translated by Martin Chalmers

Cover illustration by Mark Gibbons

Cover design by The Fish Family

_________________________________

• THE •

ORPHANAGE

_________________________________

_________________________________

• THE •

ORPHANAGE

Hubert Fichte

Translated by Martin Chalmers

SERPENT’S

TAIL

_________________________________

_________________________________

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Fichte, Hubert

I. Title II. Waisenhaus. English

833’. 914

ISBN 1-85242-161-4

Originally published 1965 as Das Waisenhaus.

Copyright © 1977 by S. Fischer

Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, for the new German edition

Translation copyright © 1990 by Serpent’s Tail

This edition first published 1990 by

Serpent’s Tail, 4 Blackstock Mews, London N4

Typeset in 10/13pt Imprint by Selectmove, London

Printed on acid-free paper by

Norhaven A/S, Viborg, Denmark

_________________________________

_________________________________

• THE •

ORPHANAGE

_________________________________

Detlev stands apart from the others on the balcony. The orphanage children are waiting for Sister Silissa and Sister Appia to enter the dining room, look into the two deep soup pots, take two eggs out of the hidden pockets of their black habits, crack the eggs on the edge of the pot, let egg white and yolk drop into the soup, wipe the two halves of each shell with a finger, throw the rustling egg shells into the refuse pail beside the iron stove, and quickly stir in yolk and white with the ladle before they curdle.

The red bow of the Easter lamb still lies on the plot of grass by the apse. Detlev looks over to the church yard. Detlev is already wearing his suit for the journey, the one his mother had made a year ago for his first day at school.

After the meal Detlev’s mother will come to fetch him and they will travel together through the night to his grandparents in Hamburg.

Sister Silissa combed his hair for the journey. She drew the parting with the edge of the comb, pressed a curl into place with two fingers. She put her black clothed arm around his head and pressed her face, framed by white, starched linen, against his hair.

— You’re not going to be a priest now, after all.

Frieda has promised Detlev a prayer that will convert him into being a Catholic in Hamburg, even before the war is over.

The girls are skipping. The boys are playing cards. Alfred is on the lookout at the door, for when the nuns grasp the handle on the other side.

Detlev’s face is white.

— You’re looking very pale again today, said the nuns. Sister Silissa had said :

— Detlev has beautiful large ears.

when his mother left him at the orphanage.

— Your ears are as big as Jew ears, said the teacher, before she struck him across the fingers with the split cane. The cane came apart and pinched his skin.

When Detlev was alone in the washroom — when his mother left him alone in the room at the veterinary surgeon’s or in her attic room, Detlev looked at his ears in the mirror. Sitting on the toilet, he pulled a photo of himself out of the pouch that his mother had hung around his neck after the first air-raid.

— My lips are thick.

— I have a curl in my hair.

— My face is pale.

— My chin doesn’t stick out.

— He has a receding chin, said Sister Appia to Sister Silissa. Detlev pushes himself away from the wall. He runs his fingers along the top of the balcony railing. He stops at the end rail. A small bead is lying on the rail. Grey and white.

— It’s a doll’s eye.

Detlev reaches out. He wants to pick it up. He squashes it. Green slime sticks to his fingertips.

— Detlev has picked up bird dropping, shouts Alfred.

The girls drop the skipping rope and look over to Detlev. The boys lay their cards face down on the cement floor and stand in front of Detlev.

Sister Silissa and Sister Appia step onto the balcony. Alfred hadn’t kept watch. The nuns have come into the dining room unnoticed. They hadn’t stayed by the soup pots — they cracked the eggs and stirred them into the soup without a single child hearing.

Sister Silissa discovers the cards on the floor and pinches the ears of Odel and Joachim-Devil. The nuns’ veils flutter up. The nuns bear down on Detlev.

— If only it hadn’t been there, thinks Detlev.

— And we had already tidied you up for your departure.

— If I hadn’t looked along the railing. If I hadn’t thought: That’s a doll’s eye lying there. If the bird shit hadn’t been lying there at all.

— Go and wash your hands again.

— Then Sister Silissa wouldn’t be looking angrily at me now.

Sister Silissa’s eyes are half closed. Detlev recognizes every pore in her face. Her lips are the same pink colour as her eyelids, her chin, her nose. The starched, shining linen that covers her hair, her ears, her throat, her forehead, chafes her cheeks.

— If Sister Silissa didn’t exist, then Alfred would disappear. Mummy says, Alfred has a sheep’s face.

Detlev squeezes his eyes shut. The children become all mixed up together. Alfred’s eyes don’t move. His cheeks swell. His nose breaks through in the middle. His ears move towards one another.

— If only it hadn’t been there.

Detlev’s thoughts chase one another more quickly. Sounds, smells merge with phrases, words, fragments of words, letters. Detlev is turning red.

— Detlev is turning red.

He begins to sweat. He’d like to go to sleep. He shuts his eyes completely. Detlev sees the stalk of a hazel nut.

— Alfred dug up the hazel nut and ate it. Detlev admired his mother when she looked sternly and fearlessly at Alfred. She didn’t avoid his eyes. Detlev looks at Alfred. Alfred’s eyes slide over one another, like grandmother’s fold-up spectacles, which she kept in the middle drawer of the kitchen sideboard and took out if she was baking and wanted to read a recipe.

— Are a sheep’s eyes as ugly as Alfred’s? I said, I like you Alfred. — I don’t like him. When he looks at me for a long time, he’s trying to scare me. When he’s nice to me he’s drawing me out. He tells Odel and Joachim-Devil and Shaky everything. They laugh at me. They help him. He wants to keep all the power for himself. He envies me. Detlev hears the whispering once again. It’s completely still on the balcony. The wind drops and the nuns’ black veils fall back onto their shoulders.

Alfred’s voice. In the morning. In church:

— Don’t look. Don’t watch for the signal. Be humble. If you look, you’re a hypocrite. Hypocrites go to hell.

The s

mell of urine. Hammer blows. Blows on the washroom door.

— That’s the devil. He’s hammering your coffin.

Detlev opens his eyes. He shuts his eyes. Alfred in the washroom. Alfred in the dining room. Alfred with bread. Alfred with oatmeal cake.

— Alfred has green eyes. Because he has committed mortal sins. I haven’t committed any mortal sins.

Detlev opens his eyes. He looks at Alfred. He wants to look him in the eyes. Today is the last day. Alfred looks at Detlev’s finger.

— Now Alfred’s thinking: You’ve made yourself dirty. That’s how dirty you are, on the day you leave.

Alfred looks at Detlev. Detlev looks away.

— Anna. Will Anna get convulsions when I go away? Anna will go to hell. She said so herself. Anna’s eyes are brown. There’s no white around them. I would like to look into Anna’s eyes always. Anna’s eyes are gentle. Anna will go to hell. Soon Anna’s eyes will be gone for ever. I’m going back to Hamburg with mummy.

Anna’s pigtails are black strokes on either side of her face.

— Anna’s eyes have a squint from falling. Her head is as lopsided and twisted as the head of Peter’s doll. Perhaps she lay in the ruins. Anna betrayed me to Alfred, because she was afraid of going to hell. Then she was afraid of going to hell yet again, because she had betrayed me to Alfred; then she betrayed Alfred and Odel and Joachim-Devil to me. If I hadn’t looked along the railing, I wouldn’t have put my hand on the bird shit, Alfred wouldn’t be there, Sister Silissa wouldn’t be there, Anna wouldn’t have told Alfred anything, the devil wouldn’t have come.

Detlev sucks in air. He draws up his shoulders. He stretches his back. He doesn’t breathe with a gurgling stomach like Odel. He breathes like Joachim-Devil, like Alfred, Anna, Sister Silissa whose shoulders thrust upwards when they breathe in.

Frieda steps onto the balcony.

— Frieda is a real example. Her blonde pigtails. The colour of her eyes. Her ears are not too large, Sister Appia said. Detlev breathes more quickly. A vein twitches from side to side under his chin.

Detlev is expecting the prayer of conversion from Frieda. She goes and stands in the last row of children.

— Frieda breathes with her stomach.

Detlev can’t push the air back out of his throat. He sucks in more and more air. He can’t get rid of the air again. Detlev’s tongue beats against his gums.

— Frieda is Alfred’s sister. Now Frieda will betray me after all.

She had cut his nails and buttoned his braces back onto his trousers when he had been to the lavatory.

— Frieda is an Aryan type, his mother had said to Sister Appia.

— Frieda knows a prayer the others don’t know. Sister Silissa doesn’t know it. Neither does Anna, not even her brother, thought Detlev at Alfred’s confirmation, when Frieda promised him the prayer that was to change him into a Catholic far away from the orphanage in Scheyern.

— If I hadn’t put my hand on the bird shit, if Sister Silissa and Sister Appia weren’t there, if Anna wasn’t there, there wouldn’t be a balcony at all. Detlev imagines the church square and the orphanage without a balcony. The railings grow thicker and turn into a wall. The bars change into black lumps. The children bunch together with the nuns and turn into grandfather’s compost heap.

Detlev flies high in the air like the red balloon at the Hamburg fair before the war. Detlev flies high above like a bomber.

Detlev looks down on the four columns of the balcony. He presses the railings down with his finger and the balcony falls off like a block from his box of building bricks.

— I want to play with my box of building bricks in Hamburg. The walls fall over. Detlev pulls the blocks out of the ground.

— If there’s no balcony, there’s no wash house either.

Every Tuesday the nuns float through the clouds of steam. Detlev hears the sound of soapy cloth on the wash board.

— Don’t waste the green soap.

Detlev knocks down the wash house walls from above. He pushes the dormitory away. He strikes the cellophane panes with his fist. He tramples on each white beam, lays them bare. He throws out the beds. Erwin’s bed.

Erwin screamed like Herod: Not on me. Joachim-Devil’s bed. Odel’s wet bed. He bends Alfred’s bed back and forward. He snaps it in half. Detlev breaks off the wash rooms. In the mornings Joachim-Devil hopped round in a circle there and farted at every hop.

Detlev knocks down the lavatory. He lifts up the slippery, cold tiles, knocks down the walls they wiped their fingers on when they cleaned themselves without paper.

Detlev knocks out the doors, demolishes the entrance hall, overturns the girls’ dormitory, squashes the crockery cupboard in which Peter and his doll — Youking — had been bombarded in Detlev’s place.

Detlev forgets to destroy the dining room. He carefully lifts the enclosure aside.

No one knows what happens in there.

— When they’re dead, they’re kept in the enclosure.

— Sometimes angels fly in and out.

— At night the devil climbs in and performs impure acts at the foot of the beds.

Detlev rolls up the garden. There’s a hole in the garden. Alfred had sneaked after him and watched him planting the hazel nut. Every morning before mass, Detlev ran out to feel if it was beginning to grow. Alfred sneaked after him every time. The nut pushed a red stalk out of the earth. Alfred tore it out, broke off the stalk, threw the shell away, wanted to eat the rest of the nut. He spat it all out again. Detlev found the dead stalk, the dried spittle, the chewed nut.

Detlev wants to pack up the church. He’s afraid of the crash when the church tower falls down.

— Then I’ll wake up.

High above the spire buzzed a silvery enemy reconnaissance plane.

— If there was no orphanage and no parish church, then the whole of Scheyern wouldn’t exist.

Detlev raises his hands. The bird dropping doesn’t fall off. Detlev rubs his hands together. Detlev clasps his fingers and rubs.

— He’s praying. He can’t help doing it. He prays like a Protestant.

— Alfred hasn’t seen anything. He doesn’t shout anything. Detlev squashes the dropping between his fingers. Detlev puts his palms together. He wants to rub away the green slime without the orphanage children noticing.

— Detlev is a heretic. He puts his hands together with shit on them.

— No. Alfred doesn’t shout anything.

Detlev smears the dropping over his hands. He places his hands against one another with outstretched fingers. He crosses his thumbs.

— Detlev prays like a Catholic. Detlev soils our Holy Catholic Faith.

When Sister Silissa said the Ave and the Paternoster, she tapped her forefingers against one another, then she tapped her middle fingers against one another, then her ring fingers, her middle fingers, her forefingers, forwards, backwards, until the prayer was finished.

— Catholics hold their hands differently from Protestants when they pray. If I hadn’t put my hand on the shit, everyone wouldn’t be looking at me.

Detlev leans against the railing. He wants to stop thinking about all the things that wouldn’t exist, if the very smallest thing didn’t exist — the bird dropping. He wants to scratch himself.

— Detlev is scratching himself with the bird shit on his hand.

— Detlev has Saint Vitus’s Dance.

— Anna’s illness is infectious.

— Detlev has to go to hospital for observation. He’ll be locked up. He won’t be allowed to travel to Hamburg. There’s an itch between his eyes, behind his ears, on the back of his neck. The objects move up so close to him that their corners jab into his eyes.

Detlev squeezes his eyes together. The orphanage children float past one another like the hooting tugs in the harbour. Detlev sees black jagged spots,

— like the crumpled carbon paper in the municipal finance office.

— Carbon paper must be destroyed after use in cas

e of espionage,

like the partly decayed leaves Detlev had collected beneath the quince tree in his grandfather’s garden. He held them up against the brightest spot in the clouds. The little ribs were left, and a few wet pieces. He had never been able to make out a head or a figure in a leaf.

— If Aichach and Steingriff and Scheyern didn’t exist, I would never have come to this orphanage.

Detlev’s case had been collected by a nun with the handcart. A man placed his mother’s chair, her hat box on a tricycle. They were to be taken to the new room. The new room was too small to accommodate Detlev together with his mother. Detlev walked down the high street with his mother : The stonemason. The café. The cobbler. The grammar school. The town wall. The war memorial. The bank. The primary school. The gauleiter’s office. The market place. The other café. The smithy.

— Here is the municipal finance office. You know it just as well as I do.

— Here is Saint Joseph’s Fountain. We walked past it on the first day.

— Do you still remember?

— You said we were especially lucky to be evacuated to Scheyern.

— The evacuation is already over. It doesn’t last very long. The air in a small town is healthier, that’s why I’ve started work here. But it’s no longer possible to find a room for both of us. We must accept that. We’ve already moved nine times. Moved nine times, Kriegel keeps on repeating. Moved nine times. Moved nine times. As if he had to pay for the move. Then the finance office found me a room after all. If it had been up to Kriegel, we should have gone back to Hamburg right away. It’s a small room. The war is to blame, Detlev. When I saw them marching — even before the war

The Orphanage

The Orphanage